Think golf is a quiet, gentlemanly game? You’re probably right – but that’s not how it appears in literature. Peter Robins investigates.

According to Stephen Potter, golf is 'the games game of games games'. What he means is that golf offers more scope than any other sport for distraction, snobbery, rule-book-lawyering, psychological warfare, and all the other methods of near-cheating described in his 1947 manual Gamesmanship. It’s a bold claim. But to judge by golf’s place in literature, it’s also justified. The sample may be biased, of course. In 1954, literary golfer Bernard Darwin contributed a volume on golf to Burke Publishing’s ‘Pleasures of Life’ series. His message: apart from PG Wodehouse, there is no such thing as golf in fiction. At least, not in good fiction. Golf is ‘unsuited to the novelist or indeed to the writer of short stories’. There is only one available plot – ‘rival suitors playing off for a lady’s hand’ – and it isn’t even a good plot.

The sample may be biased, of course. In 1954, literary golfer Bernard Darwin contributed a volume on golf to Burke Publishing’s ‘Pleasures of Life’ series. His message: apart from PG Wodehouse, there is no such thing as golf in fiction. At least, not in good fiction. Golf is ‘unsuited to the novelist or indeed to the writer of short stories’. There is only one available plot – ‘rival suitors playing off for a lady’s hand’ – and it isn’t even a good plot.

Darwin was a civilised man, instrumental in getting etiquette added to golf’s rulebook. The game he believed in was gentlemanly, even heroic. The golf of novelists and poets, on the other hand, is tainted by greed and racked with malice. But tension is good for fiction – and writers have found plenty of tension in golf. As you might expect from this theory, the poets are the most divided group, being least in need of narrative tension.

There are the likes of Kipling, who included lines on the similarities between golf and art in his Verses on Sports, and Betjeman, whose Seaside Golf is a sunny tribute to a ‘quite unprecedented three’ in idyllic surroundings:

Lark song and sea sounds in the air

And splendour, splendour everywhere.

The most-quoted piece of golfing poetry, however, is a 1914 quatrain by Sarah N Cleghorn, which uses the game as an image of the idle rich:

The golf links lie so near the mill

That almost every day

The laboring children can look out ~

And see the men at play.

And in TS Eliot’s Choruses from ‘The Rock’, golf becomes a symbol not of idleness but of a Godless, doomed society:

Their only monument the asphalt road

And a thousand lost golf balls.

Even Wodehouse, not given to a grim view of human nature, finds golf an excuse to darken his humour. In the preface to The Clicking of Cuthbert (1922), his first collection of golf stories, Wodehouse claims to be writing as ‘a very nearly desperate man, an eighteen-handicap man who has got to look extremely slippy if he doesn’t want to find himself in the twenties again’. The chief source of jokes in Clicking, and in its sequel The Heart of a Goof, is a vision of golf as an obsession, something between a religious cult and a mental illness. When Wodehouse’s golfers are bad, it destroys their confidence. When they’re good, it makes them intolerable.

Either way, they play golf all the time. You can hear their work lives falling apart in the distance: we are told, in wonder, of a golfer who would often ‘go to the trouble and expense of ringing up the office’ to say he wouldn’t be in.

And since they’re often caught up in Darwin’s one available plot – competing for the love of a woman – they have few scruples. They ferry one another’s balls by car to the other end of town, they bribe caddies and then hire private detectives to catch each other bribing caddies.

Wodehouse has golf provoke rage, despair, marriage breakdown and the severing of long friendships, as well as the formation of innumerable romances. His golfers swear by golfing heroes and dream of naming children after them: ‘Abe Mitchell Ribbed-face Mashie Banks’ or ‘Harry Vardon Sturgis’ (also JH Taylor Sturgis, George Duncan Sturgis, Edward Ray Sturgis, Horace Hutchinson Sturgis and little James Braid Sturgis).

The game’s effect on his narrator, meanwhile, is to turn him into a lethal bore. When other denizens of the Marvis Bay golf club see the Oldest Member coming, they leap up ‘with a whirr like a rocketing partridge’. It’s all good, funny, light, mock-heroic stuff. But it doesn’t leave you with a high estimation of the sanity of golfers.

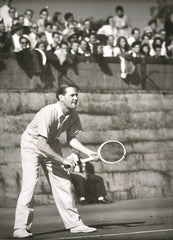

The greatest moment for dysfunctional fictional golf, however, comes in Ian Fleming’s Goldfinger (1959). The match between Bond and Goldfinger stretches over three chapters, roughly the same number it takes to attack and enter Fort Knox. There is $10,000 at stake. The course is Sandwich, where Goldfinger, we’re told, practises with a professional every day (nobody else will play with him). Bond, by contrast, hasn’t been there for years, but the staff respond to his arrival as if he were the long lost son of the manor: ‘Why, if it isn’t Mr James!’

The class warfare continues. There is a pretty contest between U and non-U golfing equipment, with Bond’s hickory-handled putter trumping Goldfinger’s ‘brand new set of American Ben Hogans’. Bond wins on fashion, too: ‘Goldfinger had made an attempt to look smart at golf and that is the only way of dressing that is incongruous on a links.’ Then we move to the main subject of the masterclass: how to cheat. Here are dozens of ways to disconcert your opponent, from dropping your driver on his stroke to standing in his light. But it’s when the caddies become involved that the real difference in class emerges. Goldfinger has to bribe his caddie to cheat for him; Bond’s offers better cheating for free.

Might this psychosis and sharp practice simply reflect the corrupt, modern game? The origins of golf go back a long way. A golf-like game, paganica, was played in Roman times, and it seems innocent enough when mentioned in Martial’s Epigrams. And there is evidence of ‘Kolf’, a game rather closer to modern golf, in 15th century Holland. But more interesting is the anti-golfing legislation that was enacted in Scotland in 1457. It reflects a Wodehousean problem: men were playing frivolous games like golf rather than practising archery. For the first big literary appearance of golf, you have to wait until 1771, when the touring party in Smollett’s Humphrey Clinker reaches Edinburgh. They see golf as practised by the first recorded club, Edinburgh’s ‘Honourable Company of Gentleman Golfers’ (founded in 1744 – the more influential Royal and Ancient golf club in St Andrews was to follow in 1754). The game seems nice enough: Hard by, in the fields called the Links, the citizens of Edinburgh divert themselves at a game called golf, in which they use a curious kind of bats, tipped with horn, and small elastic balls of leather, stuffed with feathers… you may see a multitude of all ranks, from the senator of justice to the lowest tradesman, mingled together in their shirts, and following the balls with the utmost eagerness.

No snobbery, you’ll notice. There is a little drunkenness: we’re shown a group of eightysomething lifetime golfers, who have never gone to bed ‘without having each the best part of a gallon of claret in his belly’. On the whole, though, this is golf as local colour, and therefore positive. Smollett was Scottish, but his narrator here is a young Welshman, and his notes on golf appear in the same letter as his notes on haggis, oatcakes, and the beauty of Scottish women. We’re denied a non-Scottish picture for quite some time. Golf’s temperamental equipment – the wooden-shafted clubs, the feather-stuffed balls – required building and maintenance by craftsmen, and limited its potential for export.

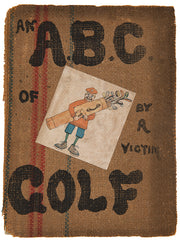

The change comes in 1852, with the introduction of a ball made from the proto-plastic gutta percha. The ‘gutty’ was cheap and easy to make, and withstood wet much better than the old ‘feathery’. Scottish golf continued to expand, and golf clubs began springing up in England. By 1887, there was enough demand for a golfing annual to start publication; textbooks and anthologies followed. When, in 1902, the introduction of a further-flying rubber-cored ball made golf a more forgiving game to learn, conditions were set for a boom.

And that created the conditions for a less practical golfing literature – books such as the Canadian Arnold Haultain’s The Mystery of Golf(1908). First published in a limited edition of just 440 copies, this employs Edwardian literary dash, mock-Caxtonian marginal glosses and late-Victorian neuroscience in an attempt to explain golf’s grip on the imagination. There are three great mysteries, Haultain says: metaphysics (dealt with by the Germans); ‘the feminine heart’ (dealt with by the French); and golf (still mysterious).

Haultain’s golf-world retains its innocence. His golfers are red-coated gents, and their game gets some of its appeal from a position as an elite sport, ‘uncontaminated by either “bookies” or “bleachers”’. It doesn’t even ask for gate money.

Golf is fascinating, Haultain says, because it makes exceptional demands in three different ways: the physical variety of the different strokes; the mental difficulties of getting them right without the stimulus of a moving ball; and the social subtleties of long, nervy contest. Here we can see the novice golfer discovering how ‘the character of his opponent and the quality of his opponent’s play exercise a most extraordinary influence over him’. Haultain’s emphasis on the disparity between golf’s simple aim (ball into hole with stick) and its complicated techniques also informs later books: it is one of the things that makes golf so good a comic humiliation.

But for John Updike, probably the most accomplished recent fictionaliser of golf, such humiliation can serve a higher purpose. Golf is nothing short of ‘moral exercise’: the one time when even cosseted and flattered bosses must face up to their inadequacies. Updike’s golf – in his earlier books, at least – is a more egalitarian activity than Haultain’s: clergymen and businessmen and writers hacking around public courses. As public courses get busier, and he and his characters get richer, private clubs appear.

Rabbit Angstrom – Updike’s most long-running character, and his most frequent golfer – plays most of his golf after making it as a car dealer – his rounds are a way of not talking to people. Then there is the pastor who wants to persuade him back to his first wife and the old friend whose wife he borrowed. Flashes of sporting beauty stand as a contrast to the mess of life.

That’s not to say that golf can’t still bring out social snippiness. Look at what Nicholson Baker does with it in U and I, his dizzying confession of Updike-envy. Told at a party that another writer (Vietnam chronicler Tim O’Brien) plays golf with his hero, Baker goes into a brilliant, chapterlong flat spin: ‘It didn’t matter that I hadn’t written a book that had won the National Book Award, hadn’t written a book of any kind, and didn’t know how to golf: still, I felt strongly that Updike should have asked me’.

This is reassuring. For all that Tiger Woods is opening it up, golf remains a game with the power to divide, to humiliate, and to bring forth jealousy – even in those who don’t play it. Which should keep golf-lit an interesting genre.

Discover more: Ball Games

Leave a comment